The origins and history of the Egyptian Mau by Melissa Bateson

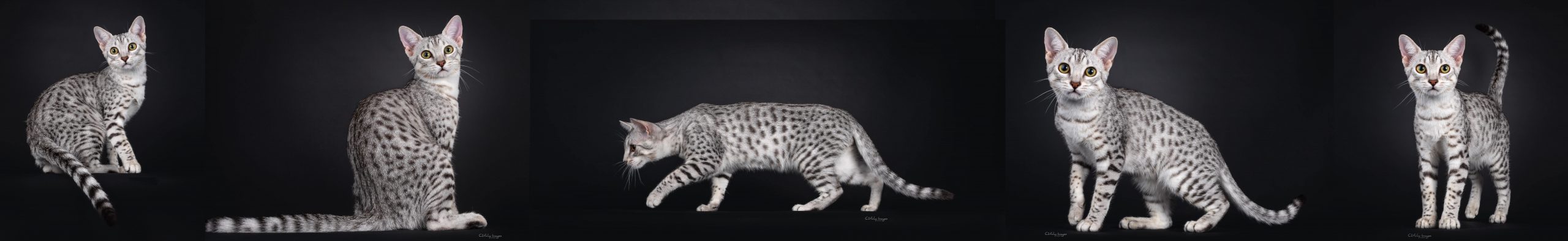

Introduction The Egyptian Mau is an elegant spotted cat of moderate foreign type that bears a striking resemblance to the cats depicted in the art of the ancient Egyptians. Unlike some of the more recent attempts to recreate the look of these primitive cats by hybridizing established breeds, the Mau is a natural breed derived from the modern street cats of Egypt. Part of the attraction of the Egyptian Mau is the romantic history of the breed and the very real possibility that Maus trace their ancestry directly back to the cats first domesticated by the ancient Egyptians. My aim in this article is to explore what we know about the origins of spotted cats in ancient Egypt and their possible links to the modern Egyptian Mau as we know it today.

Ancient history of Egypt and the Egyptian Mau

To trace the full history of spotted Egyptian cats we have to start in ancient Egypt around 4000 years BC when the first permanent settlements began to appear along the Nile and small cats of the genus Felis first began their close, and long-lasting association with man. It is probable that the first domestic cats (whose latin name is Felis sylvestris catus) evolved from small wild cats living in Egypt at that time. These wild cats would initially have been attracted to human settlements by the abundant quantities of rodents that would have infested the houses and grain silos of the ancient Egyptians. It has been estimated that a feral cat needs to kill approximately 1,100 small animals per year to survive, so it would clearly have benefited the Egyptians to encourage the presence of these cats. Cats would have also endeared themselves to the Egyptians by killing other dangerous vermin such as snakes and scorpions. It is therefore likely that the early association between cats and man started as a symbiotic relationship that was rapidly recognized and cultivated by the ancient Egyptians.

The most likely candidate for the ancestor of the domestic cat is a small wild cat similar to the modern day species known as the North African wild cat, Felis sylvestris libyca.

This small cat measures about 600mm from nose to tail tip, and is long legged and lightly built with large, non-tufted ears. The coat colour varies considerably from rufous brown to sandy fawn or even silvery grey, and the coat pattern is similar to a broken mackerel tabby with a darker spine line, ringed tail, black tail tip and broken striped markings on the body. In general appearance therefore, libyca is not dissimilar to modern-day domestic cats and specifically Egyptian Maus. The domestication of libyca occurred sometime between 4000 and 2000 BC. The earliest evidence for an association between cats and humans in Egypt comes from a grave dated around 4000 BC. The grave contains the remains of a man, some tools, a gazelle and also a cat. The tools indicate that the man was probably a primitive craftsman, the gazelle may have been intended as food for the afterlife, and the cat at his may have been accompanying him as his pet. Unfortunately it is impossible to tell from the bones whether the cat was wild, tame or domesticated.

The oldest certain images of cats in ancient Egypt occur as hieroglyphs carved on a fragment of temple wall found to the south of Cairo and dated around 2200 BC. However, because the images are simple outlines and their context is unclear, they do not reveal much about the appearance of the cats or their state of domestication at that time. The first cats start to appear in Egyptian art from around 2000 BC, and give us a unique window onto the growing connection between cats and man. From 1900 BC the cats depicted in art are often in domestic contexts such as for example a bas relief from Coptos dating from about1950 BC that shows a cat sitting underneath a womans chair. Indeed, cats depicted sitting underneath the chairs of women are a recurrent theme in Egyptian Art, and may symbolize the fertility of the woman and the association of both the cat and the woman of the house with the goddess Hathor. By 1450 BC cats are commonplace in paintings of domestic scenes. Cats occur particularly frequently in the art of the New Kingdom (1570-1070 BC) and again in the Late Period (1070-332 BC). A second recurrent theme in Egyptian art is the depiction of cats pictured in the bird-filled marshes in the company of Egyptian hunters.

The cats are sometimes pictured with birds in their mouths, which has lead to the suggestion that the Egyptian may have used cats either to flush birds out of the marshes or possibly to retrieve the carcasses of the birds they killed. In most cases, the cats depicted in Egyptian art bear a strong resemblance to the modern Egyptian Mau. Like the modern Mau the Egyptian cats are of elegant build with large ears and eyes. These cats are also undoubtedly tabbies as evidenced by the spotted and striped markings depicted in many of the images. One problem in trying to pinpoint when cats became domesticated comes from the fact that the ancient Egyptians did not have different words to distinguish between wild and domestic cats; all cats were referred to simply as ‘(s)he who mews. In demotic this was miu or mii and in the later coptic emu or amu.. The word ‘Mau’ is derived from one of these ancient languages, and simply means cat.

Cats assumed great importance in Egyptian religion from about 2000 BC onwards. From about 1500 BC it was believed that the sun god Ra could manifest himself in the form of a cat, the ‘Great Tomcat’. Each night Ra would journey to the underworld, confront his enemy the snake demon Apophis, kill the snake with a knife and thus ensure the return of the sun the following morning. Many ancient Egyptian paintings depict Ra in the form of a spotted cat slaying Apophis. By 945 BC the cat had become associated with another goddess, Bastet, and sacred cats kept and bred in temple catteries were worshipped as living manifestations of the goddess. The popularity of this cult of Bastet continued for over 1500 years into the Roman era (to 330 AD). Many beautiful bronze sculptures of cats survive from this period, and with their long elegant limbs, high shoulder blades and level brows they are strikingly similar to modern Maus.

When a cat died in a private house the inhabitants of the house would mark its death by shaving their eyebrows. Dead cats were taken to the capital city of Bubastis where they were embalmed, mummified and buried in sacred repositories, in the hope that they would accompany their owners into the afterlife. Just as with human mummies, the wrappings of the cats were often painted with their features and other elaborate designs. Some cats were even given limestone sarcophagi or wooden cat-shaped coffins, and a few had life-like bronze face masks. Cat mummies date from around 1000 BC, and have provided much important information about the ancient Egyptians’ cats. Of the mummies that have been unwrapped, several have revealed the spotted tabby pattern characteristic of modern Egyptian Maus. There is therefore abundant evidence that elegant, spotted tabby domestic cats were common in ancient Egypt.

There seems little doubt that the Romans were responsible for taking spotted cats from Egypt to Italy and possibly other parts of Europe probably in the early centuries AD. Spotted cats closely resembling Maus in both markings and body type are clearly depicted in a number of Roman mosaics including one found at Pompeii. Domestic cats of Egyptian origin probably interbred with the stockier, longer-coated European wildcats (Felis sylvestris sylvestris) and thus gave rise to the Northern European domestic cats we know today.

Modern history of Egypt and the Egyptian Mau

Here is a cat photographed amongst the items on a stall next to Naguib Mahfouz Cafe in Khan al-Khalili. it is interesting to note the proud stance and inscrutable stare is so like the statues from Ancient Egypt.

The domestic cats of modern Egypt seem to have retained many of the characteristics of their ancestors, and bear a close resemblance to the cats depicted in ancient Egyptian art. In a recent photographic portrait of the ‘Cats of Cairo’, photographer Lorraine Chittock depicts the modern Egyptian cats as having elegant body type, modified wedge-shaped heads and large ears. Although, the cats come in a range of colours not permitted in modern Maus including red and white, there are many tabbies represented, and these are predominantly of the spotted tabby pattern characteristic of both the ancient Egyptian cats and the modern Egyptian Mau. The brown tabbies pictured tend to be of a warm brown hue more reminiscent of the bronze Mau than of the darker, cooler-coloured brown tabbies of Northern Europe.

It is difficult to find much information concerning the breeding of pedigree Egyptian cats in Europe before World War II, however, Egyptian-type cats were certainly bred in France, Italy and Switzerland in the first half of the 20th century, presumably from cats imported from Egypt and the Middle East such as those recorded by Lorraine Chittock. Marcel Reney in Nos Amis Les Chats published in France in 1940 gives a clear description of the Egyptian foreign short-hair as a tall, slim cat with a modified long head and resilient coat. The standard for the pattern describes a spotted tabby with numerous spots. Spots were to be round or oblong, clearly outlined, and must not form lines. This description is very similar to that of the Egyptian Maus we know today. During World War II the majority of cat breeds declined in Europe with the Egyptian Mau facing near extinction. We owe the survival of the modern Egyptian Mau to Nathalie Troubetskoy, an exiled Russian Princess whose story adds another romantic dimension to the history of the breed.

Troubetskoy, born in 1897 in Lublin, Poland was a member of an influential Russian family. She studied art and medicine in Moscow and after serving as a nurse in Russia towards the end of World War I she moved to England where she lived and worked for 20 years, nursing, lecturing and broadcasting. Shortly before World War II she moved to Rome where she served as a nurse to the US 2675th Regiment apon its arrival in Italy. The story goes that one day in the early 1950s, while Troubetskoy was living in Rome, a young boy presented her with a silver-spotted female kitten that he had been keeping in a shoe box . Apparently, the kitten had been given to the boy by a diplomat working at one of the Middle East embassies. Troubetskoy was immediately taken with the striking appearance of the kitten and sought to learn more about where it came from. Her research lead her to conclude that the kitten was an Egyptian Mau, a breed known on the show benches in Italy before the War, but now all but extinct. Troubetskoy became determined to save the Egyptian Mau breed and set about acquiring more cats.

She started with two cats, Gregorio, a black male, and Lulu (also sometimes referred to as Ludol) a silver spotted female. Later Troubetskoy used diplomatic contacts to increase the gene pool available to Italian breeders by importing further cats from the Middle East. One of these imports was Geppa, a smoke male. Troubetskoy’s first litter of Maus was born in Italy in 1953 followed by a second in 1954. She is reported to have exhibited these first kittens widely in Europe. In 1956 the princess emmigrated to the USA taking three of her maus with her to form the foundation for her cattery named Fatima. What is now known as the traditional line of Egyptian maus traces its ancestry back to just two of these foundation cats: an elegant and reputedly tempestuous silver female Fatima Baba, (Geppa x Lulu) and her large bronze son, Fatima Jojo (Gregorio x Fatima Baba), also known as Giorgio. The third Mau imported by Troubetskoy, a daughter of Baba and Jojo named Liza, apparently never bred. There is some evidence that the Princess imported a further male Mau sometime after arriving in the USA, however at the time of writing I have been unable to trace any definitive information about this cat. Although officially there have never been any outcrosses to other breeds, it is generally accepted amongst Mau breeders that Troubetskoy was forced to resort to some unofficial outcrossing during this early period to ensure the continued health of the breed. Three colours of Mau are present in early pedigrees, silver (black silver spotted tabby), bronze (black spotted tabby) and smoke (black smoke with a heavy ghost spotted pattern).

Given these three colours it is inevitable that self black maus were also being produced, although these don’t appear on pedigrees until some years later. These four colours, silver, bronze, smoke and black are now referred to as the traditional colours and they comprise the vast majority of Maus bred to date. There is also limited evidence that blue maus (presumably in all four basic colours) also occasionally occurred very early on, but it is only within the last couple of years that these have been registered by the Cat Fanciers’ Association, so we have no means of tracking the true origins of the dilute gene within the breed. Some breeders believe that the dilute gene and possibly also the recessive classic tabby pattern gene which occasionally shows up in litters can be traced to outcrosses used in the early years of the breed in the USA, however, these two genes are certainly present in the genepool of modern-day Egyptian street cats, so it is possible that they were carried by the first Maus to arrive in the USA.

This picture dates back to the Eighteenth Dynasty in the New Kingdom and shows an Egyptian, Nebamun, hunting in the marshes with his cat. It is a Theban tomb painting and was executed c.1450 BC or a little later.

Upon arrival in the USA Troubetskoy registered her Maus with the Cat Fanciers Federation (CFF) in which the breed soon gained championship status. Baba (formally Ch. Baba of Fatima) was the first champion in North America. The Egyptian Mau soon acquired a keen group of supporters committed to preserving the distinctive qualities of the breed. In a 1972 CFA Year Book article about the Mau Wain Harding lists the following significant catteries: Ta-Mera in CA, Almidar in MO, Tawnee in FL, Trillium in Canada, Hellgate in RI, Kattiwycke, Polka dots and Fatima in New York and finally his own cattery, Bastis, in VA. The Maus were soon recognized by other cat registeries in North America including the Canadian Cat Association and the Cat Fanciers’ Association (CFA, North America’s largest pedigree cat registry), with championship status in CFA being finally reached in 1977. The breed has expanded from its early beginnings in New York, and breeders are now found all over the USA, Canada, Japan and continental Europe, the modern European Maus being reintroduced from cats bred in North America. However, the breed did not take off in the UK, presumably because of the restrictions imposed by quarantine. There is some evidence that a couple of Maus were imported into the UK and exhibited during the 1970s, but at the time of writing I have been unable to trace who brought these cats in and what subsequently became of them.

By the late 1970s Maus began to suffer from the effects of their extremely limited gene pool, and it became imperative to find some new blood to improve the health and vigour of the breed. Jean S. Mill (Millwood) located two rufous bronze spotted tabby kittens of pronounced Egyptian type in a zoo in New Delhi. In 1980 she imported these siblings, named Toby and Tashi, into the USA. The cats were registered with the American Cat Association in 1982, and Toby’s line was accepted by The International Cat Association (TICA) shortly thereafter. The progeny of these cats bearing the Millwood cattery name were finally recognised by CFA as Egyptian Maus in the late 1980s after a battle in the course of which the cats were first accepted only to have this acceptance temporarily retracted. As I understand it, the final acceptance of the Indian lines by CFA hinged on an argument that Egyptian cats could have reached India via traditional trade routes, thus maintaining the status of the Mau as a natural breed with no allowable outcrosses. The descendants of Toby and Tashi are known as the Indian line. The Indian Maus were also used to found one of the most influencial lines of Bengal cats. The majority of modern-day Maus combine Indian and traditional lines in their pedigrees. The Indian Maus brought with them the desired health benefits of an increased gene pool and also improved the contrast and clarity of the spots when bred with traditional maus. The Indian lines are also responsible for a change in the colour of bronze maus from a sandy brown to the richer rufous coppery brown favoured in the show ring today, and the glitter gene which gives bronzes in particular a sparkling sheen. Some breeders feel that the introduction of the Indian lines also resulted in a loss of the traditional Mau head type with its characteristic, heavy brow and worried expression. It is currently a goal of these breeders to produce cats that combine the improvements in health, colour and pattern brought by the Indian lines with the stunning traditional Mau head.

Following the assimilation of the Indian lines, CFA changed its registration policy for Egyptian Maus to allow cats that meet the Mau standard and have the proper geographic origin (i.e.Egypt) to be registered as Egyptian Maus. This change in policy resulted in a new wave of Egyptian imports . In the 1980’s breeder Cathie Rowan (Rocat) brought 13 Maus from Egypt to the USA, however, as far as I am aware there was limited interest in these cats from other breeders, and descendants of these imports are not widely available. In the early 1990’s. J. Len Davidson brought in four more Maus from Egypt and has been responsible for developing these lines under the cattery name Grandtrill. Two of these imports are Giza and Wafaya, both bronze females. The Grandtrill lines are currently being used by a number of breeders in North America. Although there initially reports of problems with poor temperament and rather stripy patterns in these lines, some breeders are now using them to produce show quality Maus. More recently in 2000, French breeder Marie-Christine Hallepee (Fondcombe) imported a bronze male named Sahoure from Egypt. This cat has successfully been used to enlarge the European Mau gene pool, and some of his offspring have already gone to Mau breeders in the USA.

Maus in the UK

When I was ten years old my interest in Egyptian Maus was sparked off by a beautiful black and white photo of two silver kittens in a cat book (A Standard Guide to Cat Breeds edited by Grace Pond & Ivor Raleigh). I became determined to have one of these fascinated cats but was disappointed to learn that they did not exist in the UK. Although there was for a while a breed called the Egyptian Mau in the UK, these cats were an artificial breed created by Angela Sayer from the Siamese and were very different from the true Maus, having an oriental as opposed to foreign body type. These oriental-type cats are now called Oriental Spotted Tabbies to avoid confusion with the original Egyptian Maus.

In 1996 I went to work in America for two years and finally had the opportunity to acquire my first two Egyptian Maus, a silver female, Emau’s Isis of New Kingdom from Melanie Morgan in Virginia and a bronze neuter, Matiki’s Horus of New Kingdom from Jan and Bonnie Wydro in Atlanta, Georgia. It was a challenging business tracking down breeders from across the Atlantic Ocean via the fledging internet, and even more challenging convincing anyone that they wanted to sell a complete stranger from another country one of their prized breeding quality cats. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to American breeder Melanie Morgan who trusted me with Isis who came from her very first litter of Maus! Once I arrived in the USA, actually met some of the Mau breeders in person and gained a good reputation through showing my cats things became a lot easier. Over the next two years I added two more unrelated silver females to my collection: J’s Iris Qetesh of New Kingdom from Judith Mendelsohn in Montreal, and Emau’s Nephthys of New Kingdom from Melanie Morgan. I also acquired my first stud male a flashy silver, Sharbees Mihos of New Kingdom from Sharon Partington in Oregon. I gained a lot of valuable experience about Maus while showing my cats in CFA. Despite only being sold to me as a pet Horus achieved the title of Grand Premier and both Mihos and Qetesh achieved Grand Champion titles. During my time in the USA I bred my first four litters of Maus, three from Isis and one from Qetesh.

When I returned to the UK in autumn 1998 I brought these five cats with me. Qetesh came home pregnant by an American stud (Champion Emau’s Never Tease a Cheetah), and produced a litter of kittens while in quarantine. Of this first litter one of the female silver kittens she produced became the foundation queen for Debbie van den Berg (Singingpurrs), and I kept the only male, a smoke (Advensh Newkingdom Brutus), as a second stud cat. My original five imports have subsequently been joined by several more cats, some brought in my me and some by the growing number of converts to the breed in the UK.

In January 1999 the Maus were granted the breed reference name ‘Egyptian Mau’ by the executive committee of the GCCF, and in 2001 the breed received Preliminary Recognition from the GCCF.

Bibliography